In today’s world, where the pace of technology and human dominance over natural processes seem self-evident, mycelium offers a profound alternative perception of reality.

This delicate, underground fungal network is not merely a biological structure — it symbolizes a way the world can exist without hierarchy, not by exploiting and consuming, but by collaborating. This is precisely the kind of vision proposed by ecophilosophy — a paradigm in which the human being is not separate from the world but woven into it, co-responsible and co-present.

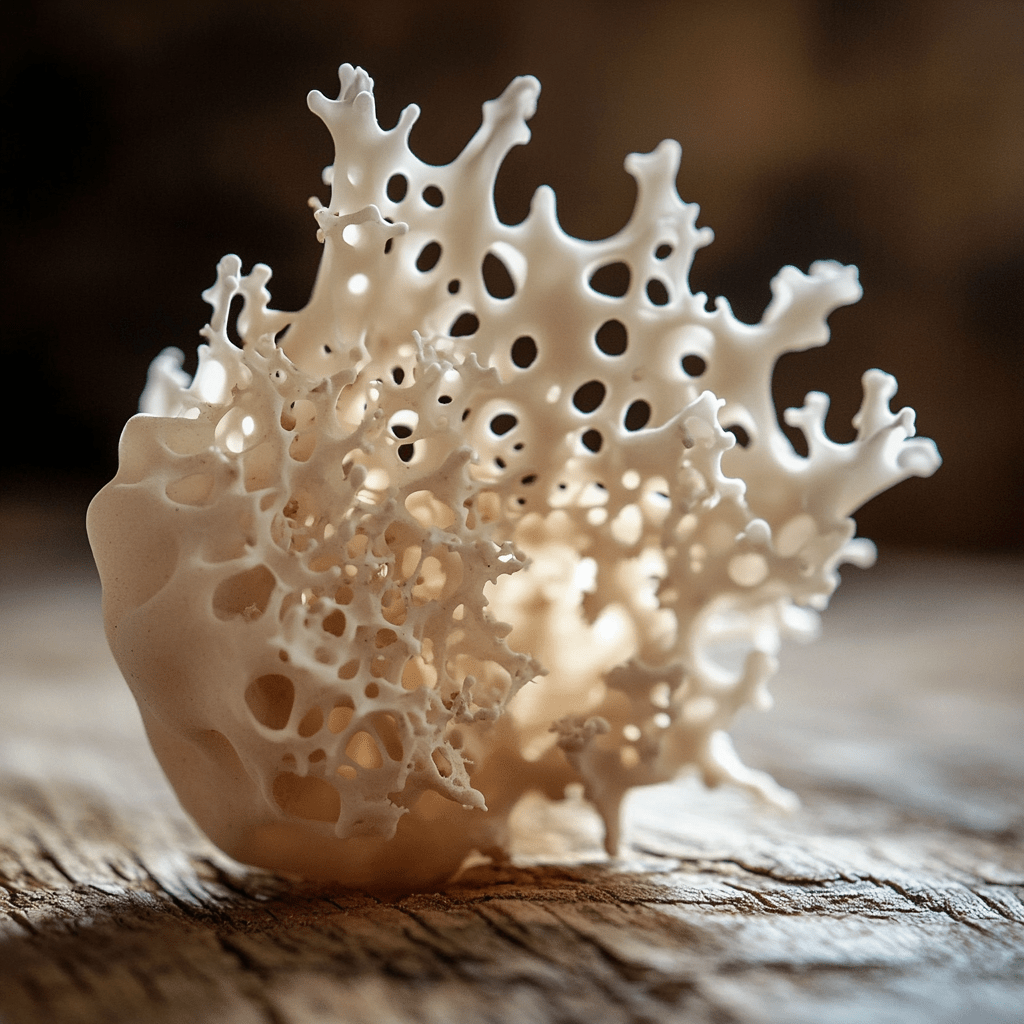

In nature, mycelium connects plants, nutrients, bacteria, and tree roots. It survives not through competition but through symbiosis. It does not create boundaries, but bridges — between plants, trees, nutrients, water, and memory. It is a web of life where essence emerges through relationships and interaction. Such an ontological view is also central to the deep ecology concept developed by philosopher Arne Næss, where the world is not reducible to objects but must be perceived as a living unity.

New materialism, especially in the work of Jane Bennett, speaks of “vital material” — matter that is not alive in the biological sense, yet carries life-like capacities: movement, transformation, sensitivity to the environment. Mycelium composites become such hybrid forms between life and non-life. They are not merely alive or non-alive — they are a fusion, where matter is no longer a passive substrate, but part of life itself.

From an ontological perspective, mycelium-based biocomposites make the traditional boundary between the living and the non-living even more visibly obsolete. The materials inhabited and transformed by mycelium — such as straw or plant biomass — may appear “inert.” Yes, they no longer perform vital functions; they are plant remnants or structurally frozen forms. Yet when mycelium grows and breathes within them, structurally transforms them, and grants them new functional properties — such as heavy metal sorption or gradual biodegradation to nourish others — these materials gain more than just form. They acquire a new experience of life.

Mycelium is also a political metaphor. It is not vertical but horizontal, and it embodies a branched, rhizomatic form of thought. It appears to represent a potential ideal of future society — decentralized and co-creative. In this model, society learns to value processes from the perspective of collective benefit, forms connections, and engages in cooperation. It could be a world where the individual is not superior to nature or others, but co-present and co-creative — just like mycelium is among.